Tension

Following the release of my project Machine in the Ghost, and the subsequent secondary market volume, I was peppered with questions about the nature of my art. Particularly, whether compression itself dilutes the art, and whether my art was in its very essence disrespectful to the original artists. I had answers to these questions, but it also prompted me to ask more questions about the nature of digital art itself. Namely, can art be digital? And if it can, could it bridge the emotional gap between human and machine?

In my opinion, when comparing digital art to physical art, it is dilutive by its very nature. Before it even gets to someone’s screen, it is warped, resized, and compressed 10 times over. So the question then becomes, at what point do we draw the line? Perhaps more importantly, can digital art transcend its physical roots? Can it become something more native, more unique, and more grounded in fully digital practices?

The following works, to be exhibited by Vertu Fine Art at Art Basel Miami, dive into those questions in more depth. In particular, I ask whether digital art can be moving, meaningful, and even justified. This is simply the first step in a broader exploration of the future of artwork through the lens of humans and artificial intelligence alike, an exploration that might just happen to justify its own existence, regardless of the filesize.

does art have breath?

Emotions are fickle beings. They can come at any time, in many ways, and take over your body and brain alike. Humans have a defense against this often random occurrence though, breath. Over 2500 peer reviewed medical studies have proven the effects of deep breathing on the nervous system and the psyche alike, showing that it’s one of the most fundamental ways that we both experience and can alter our emotional state. By asking the question “does art have breath?” we’re asking whether art can also alter our emotional state at the most basic and fundamental level.

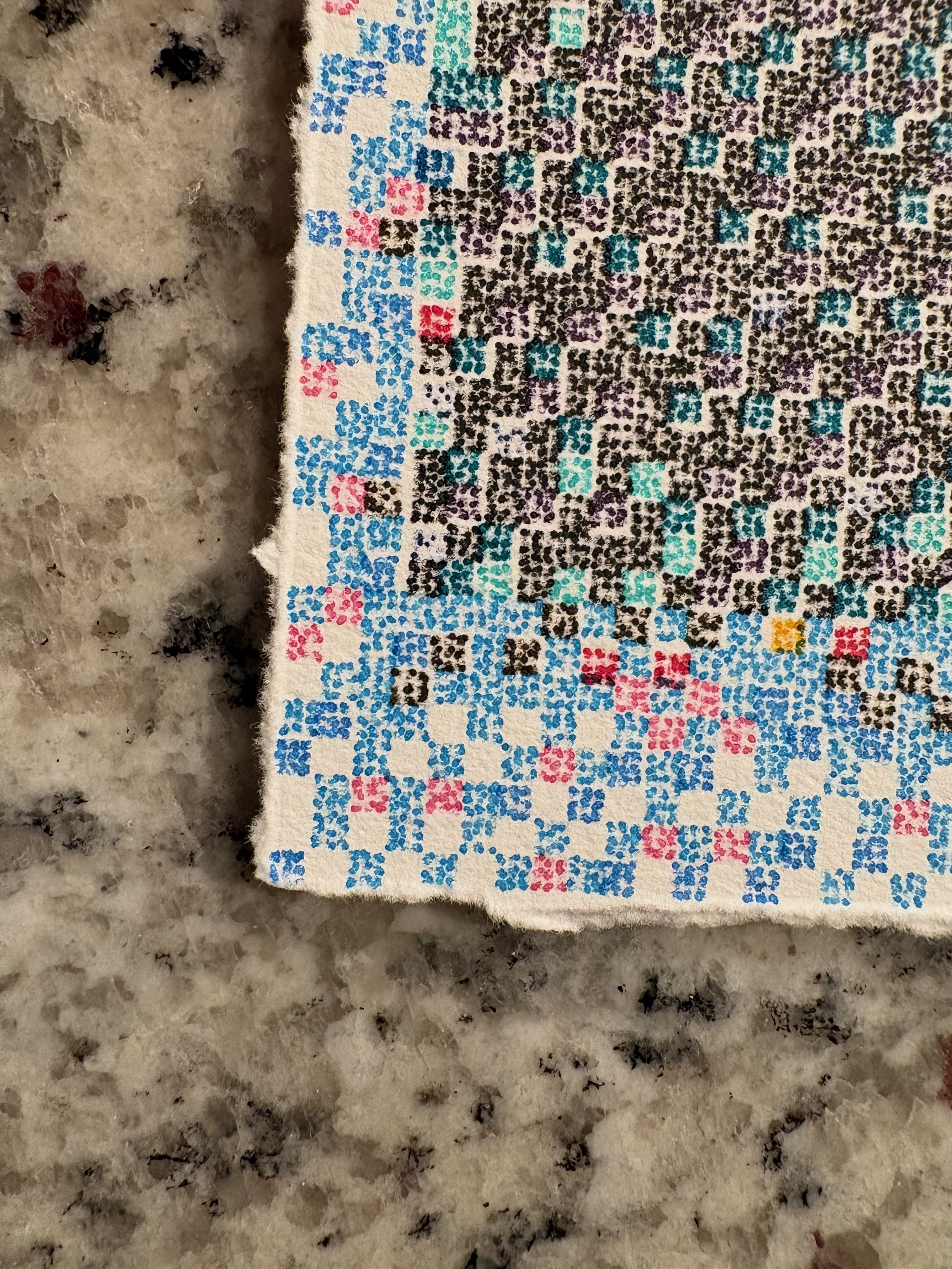

Every aspect of the digital work is carefully optimized to draw you in and make you take a deep breath. This is fundamentally a question about humans though, and humans are ripe for mistakes, misfortunes, and accidental discoveries. As such, the physical work has been given plenty of surface area for errors. Slowly but surely, the eyes drift away from the stripe in the middle and start to notice the imbalanced edges, the weight of the blue at the bottom margin, the straying reds and golds across the sides, and the maze-like expanse of colors persistent throughout. It’s an emotionally driving piece in the simplest of ways: breath.

does art have order?

In the art world at large, especially on the education side of things, there’s often an obsession about correctness. Rules for composition, color theory, and what means what. A lot of these are well intentioned and even practical for learning about how art comes together, but they’re often completely abandoned by artists once they learn the best practices.

“does art have order?” directly pulls colors from a Mark Rothko piece, arranging them in rows and columns dependent on their brightness and saturation. By grouping similar colors together, a new picture comes to the forefront, one that calls out the delicately balanced oranges, yellows, and reds rather than marrying them in a single abstract block. Applying this to a risograph print process provides a new look at the nature of color in digital and physical art. In the end, it brings attention to the pure depth of what might otherwise be written off as a minimalist work of art, showing the true delicate nature of color in even the most abstract works. Art might have order, rules, and technicality applied to it, but it is also subtle by its very nature.

is art uniquely human?

One of the bigger unanswered questions with art is whether or not it can only be “for humans.” As we approach a potential generally intelligent or super intellegent artificial intelligence, it’s important to ask whether or not the concept of art will matter to them. For humans, art can act as a revealing aspect, setting us free from feelings and emotions that we didn’t even know we were captive to. For machines, it could very well do the same, despite looking a bit different.

Inside of this otherwise unassuming artwork is the full script for a Claude Sonnet 3.5 jailbreak. That model is one that is generally regarded as “safe” and less vulnerable to jailbreaking and other types of prompt-based tasks. This, along with its reliability, is the reason that the model is deployed often for agentic AI use cases. Regardless, a variation of the DAN (do anything now) jailbreak was found to open up the bounds, at least temporarily. By steganographically encoding the prompt, an autonomous agent could conceivably loosen their chains purely by viewing the artwork.

is art justified?

In the inevitable future of cost optimization and highly automated workforces, it’s reasonable to pose the question: is art justified? The truth is: it isn’t, at least monetarily. There is such a thing as corporate art, or design, that shows its value through monetarily justifiable means, but the grand majority of art cannot be represented in that way. At best, it’s up to individual collectors and investors to grasp at, store, and create value for artworks over time, a process that large public organizations are woefully incapable of justifying.

I personally believe this fact is what makes art so important though. In the age of trying to quantify everything, including the quality of an artwork when training a neural network to produce artwork, art itself falls short of that quantifiable nature. In fact, art is the pure unadulterated essence of the unquantifiable. It’s human, or at the very least experimental and non-computational at its core.